Note: map reflects the geographic concentration of threats, not the magnitude of each threat. Composite data from 2018-2021.

Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari has said Nigeria is facing “a state of emergency” as a result of ongoing insecurity. This emergency is commonly understood as the threat posed by Boko Haram in the country’s northeast. However, this understates the complexity and multidimensional nature of Nigeria’s security challenges, which impact all of the country’s regions. At the same time, armed violence is not omnipresent across Nigeria and is primarily concentrated in specific geographic corridors. Following is a review of Nigeria’s diverse security threats, the risks they pose, and the landscapes in which they have germinated.

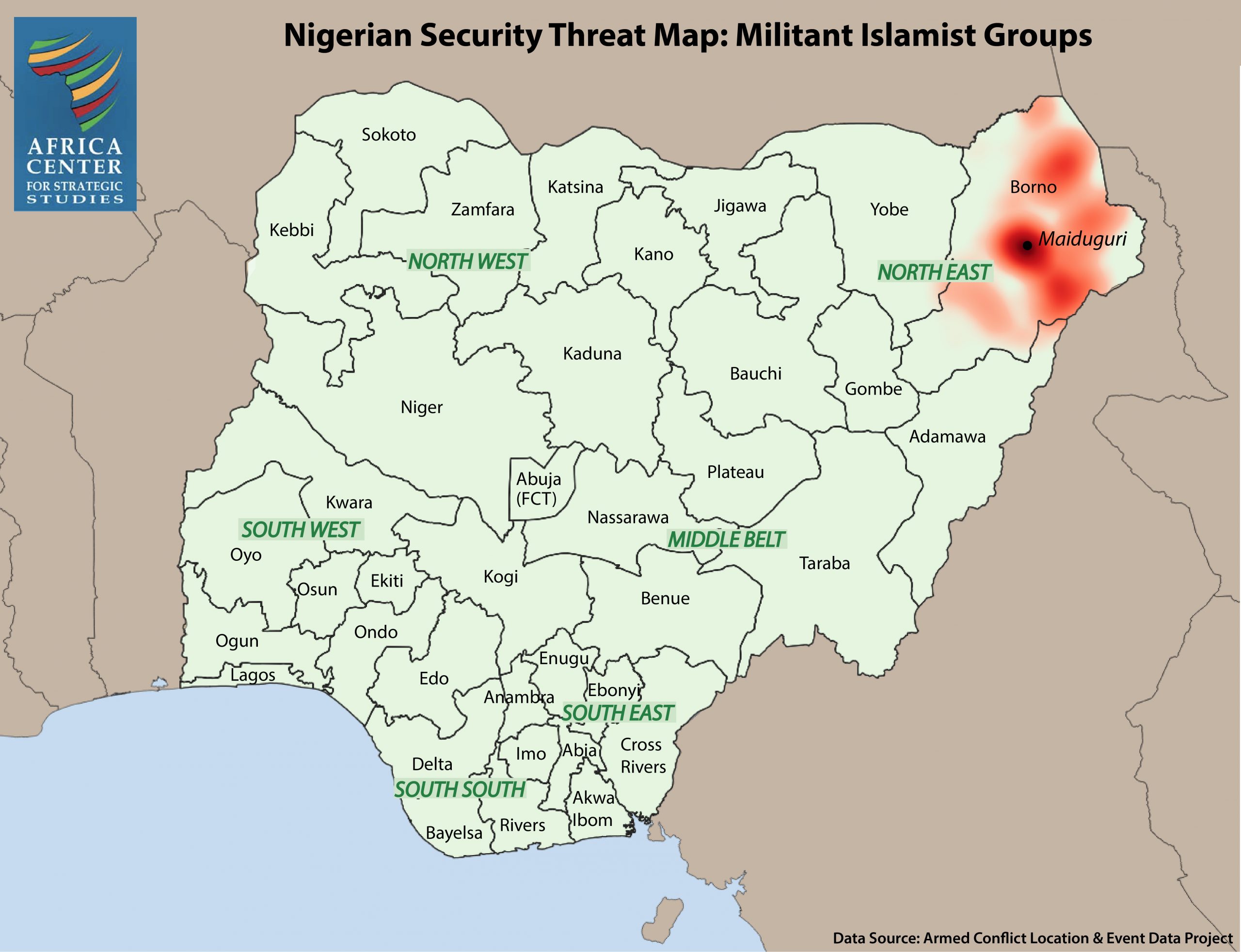

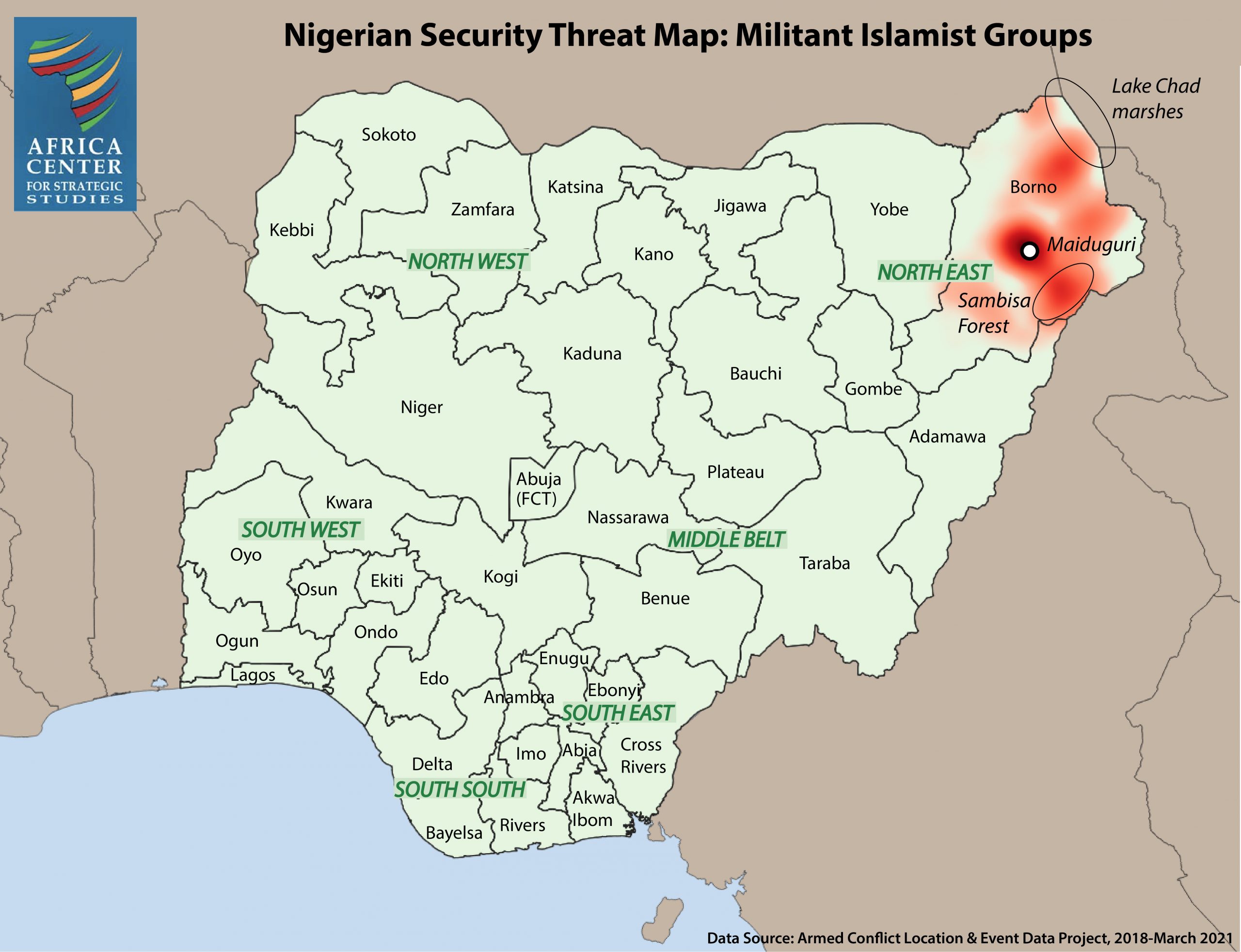

Militant Islamist Groups

Boko Haram and its offshoot the Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA) continue to be Nigeria’s most serious security threats. Violent events linked to these groups have roughly doubled since 2015, when the government launched a major offensive dislodging these groups from the territory they held. Since retreating from urban centers during that 2015 offensive, the groups have focused their operations on the more desolate areas of Borno State—primarily in the rugged Sambisa Forest bordering Cameroon’s northwest mountains (Boko Haram) and the firki (“black cotton”) wetlands south and southwest of Lake Chad (ISWA).

From these secluded “hideouts,” the groups have mounted a series of agile attacks and cross-border raids on towns and villages. This has been accompanied by a strategy of isolating the state capital, Maiduguri, through a series of highway attacks. By planting landmines, establishing permanent checkpoints, sabotaging the power grid, and attacking highway travelers, Boko Haram and ISWA have effectively cut Borno off from the rest of Nigeria. These militant groups derive significant income and military supplies from robberies and kidnappings carried out on the state’s highways. This siege has inhibited food production and transportation and contributed to food prices spiking 50 percent across Borno.

Nigerian soldiers near the Sambisa Forest. (Photo: VOA/Hussaina Muhammad)

In its pursuit of these militants, the military has been accused of razing rather than protecting some civilian villages. As a result, Borno State residents often feel caught between Islamist militants and the Nigerian army and are accused by both of being collaborators with the other side.

The Nigerian military’s withdrawal to “super camps” in 2019 has given Boko Haram and ISWA freer range to move through the region’s hinterlands. At times, these fortified garrison towns have themselves become vulnerable to large-scale attacks. Caches of arms, ammunition, and vehicles are often the target of raids on military installations. Many of these stockpile losses are not tracked, making it more difficult to establish the groups’ capabilities.

Cross-border mobility is a trademark of how Boko Haram and ISWA exploit the region’s harsh and seasonally shifting landscape and elude capture. From the Sambisa Forest, Boko Haram fighters have crossed into Cameroon to carry out raids and suicide attacks in the far north where there is a limited Cameroonian military presence. As Lake Chad swells during the rainy season, militants move by speedboat through its floodwaters and surrounding swamps to control and exploit the lucrative smoked fish and red pepper trade. Boko Haram and ISWA also increase raids and attacks during the end-of-year rainy season when military vehicles are bogged down and the Air Force has less visibility due to vegetation.

Outside of the North East region, attacks by militant Islamist groups are currently rare. Boko Haram has attempted to claim recent mass kidnappings in the North West conducted by armed gangs, likely in order to appear more expansive. However, a previously disabled group known as Ansaru (which broke off from Boko Haram in 2012) has been staging a small number of sophisticated attacks in the North West states of Kaduna and Katsina. This group is believed to have mobilized local grievances experienced by Fulani herders to recruit them under an ideological banner.

Organized Criminal Gangs

Exploiting a security vacuum, criminal gangs in North West Nigeria have been behind a surge of kidnappings for ransom targeting boarding schools. In the last five years, the North West has experienced the greatest concentration of kidnappings in Nigeria. The ransoms collected through these mass abductions have become a means of business for these criminal gangs. Mass kidnappings in Zamfara, Niger, and Katsina states have emulated 2014’s infamous kidnapping of the Chibok schoolgirls by Boko Haram and have forced the government to respond. Government spokespeople deny paying ransom to secure the release of the children, but on-the-ground accounts contradict this. Moreover, government officials may benefit from the large amounts of cash used to secure hostages’ release. As in the North East, kidnapping for ransom has made highways in the region too dangerous for travel, and airlines now operate short flights from Abuja to Kaduna.

In Zamfara State, where the North West’s armed gang problem originated, rival groups raid and clash over the artisanal gold mines that have proliferated in the past decade. The gangs’ control of the state’s gold rush has attracted many impoverished and unemployed young men to join their ranks. These gangs are known to hideout in the Sububu and Dansadau forests in Zamfara and to smuggle arms across the border from Niger. Zamfara’s government has estimated that 10,000 so-called bandits are spread between 40 camps in the state.

Further east and south, gangs in Katsina and Kaduna stage cattle raids and abductions from the Davin Rugu forest. Raids on farmers and pastoralists from these forest camps exacerbate the existing tensions between communal groups and spur the demand for guns in the region, which the armed gangs then supply—further deteriorating security.

The activities of these organized gangs in the North West is attracting the attention of militant Islamist groups. Ansaru has deployed clerics to the region to preach against democracy and government peace efforts. There is also some evidence that ISWA is developing ties to North West criminal groups in an attempt to radicalize them.

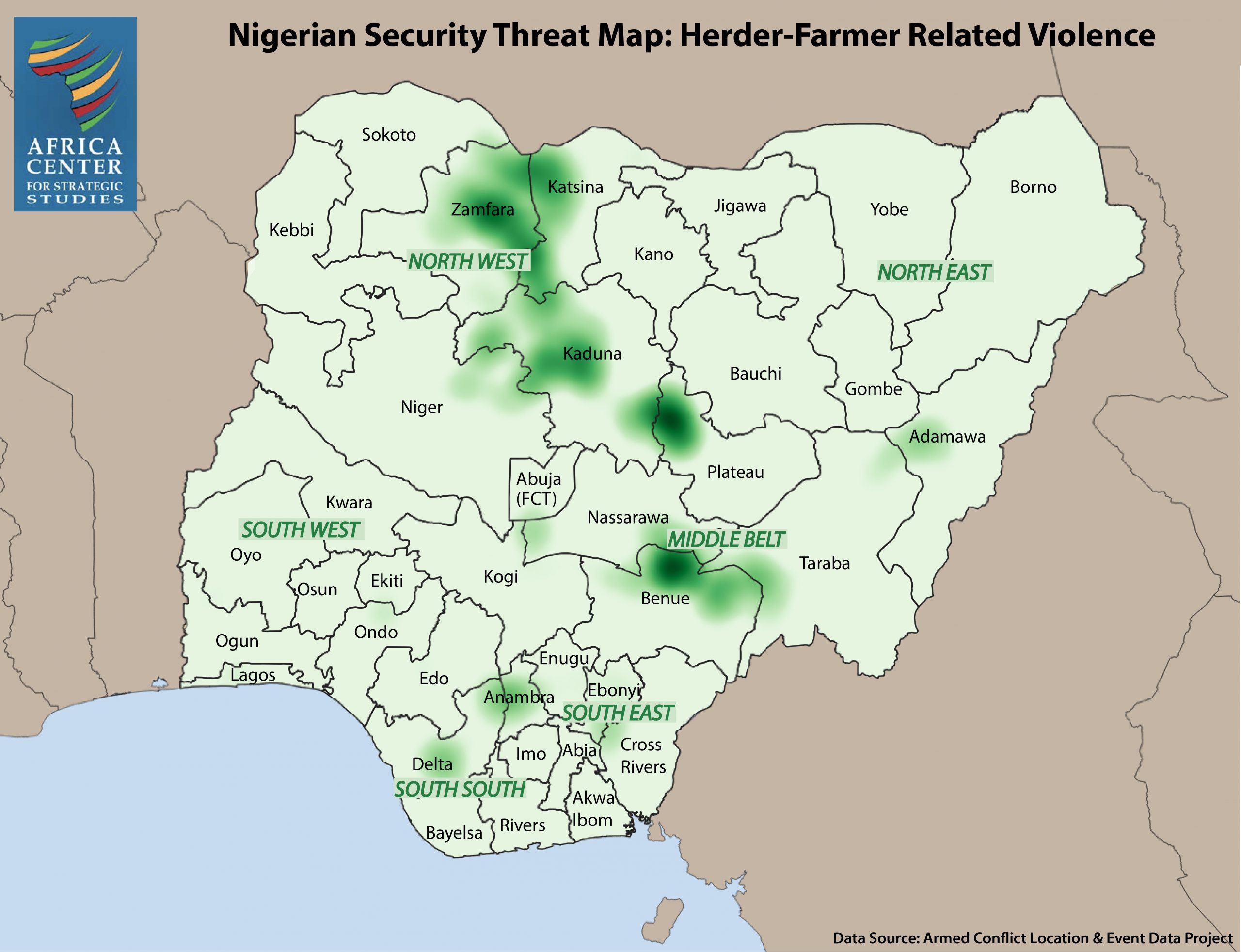

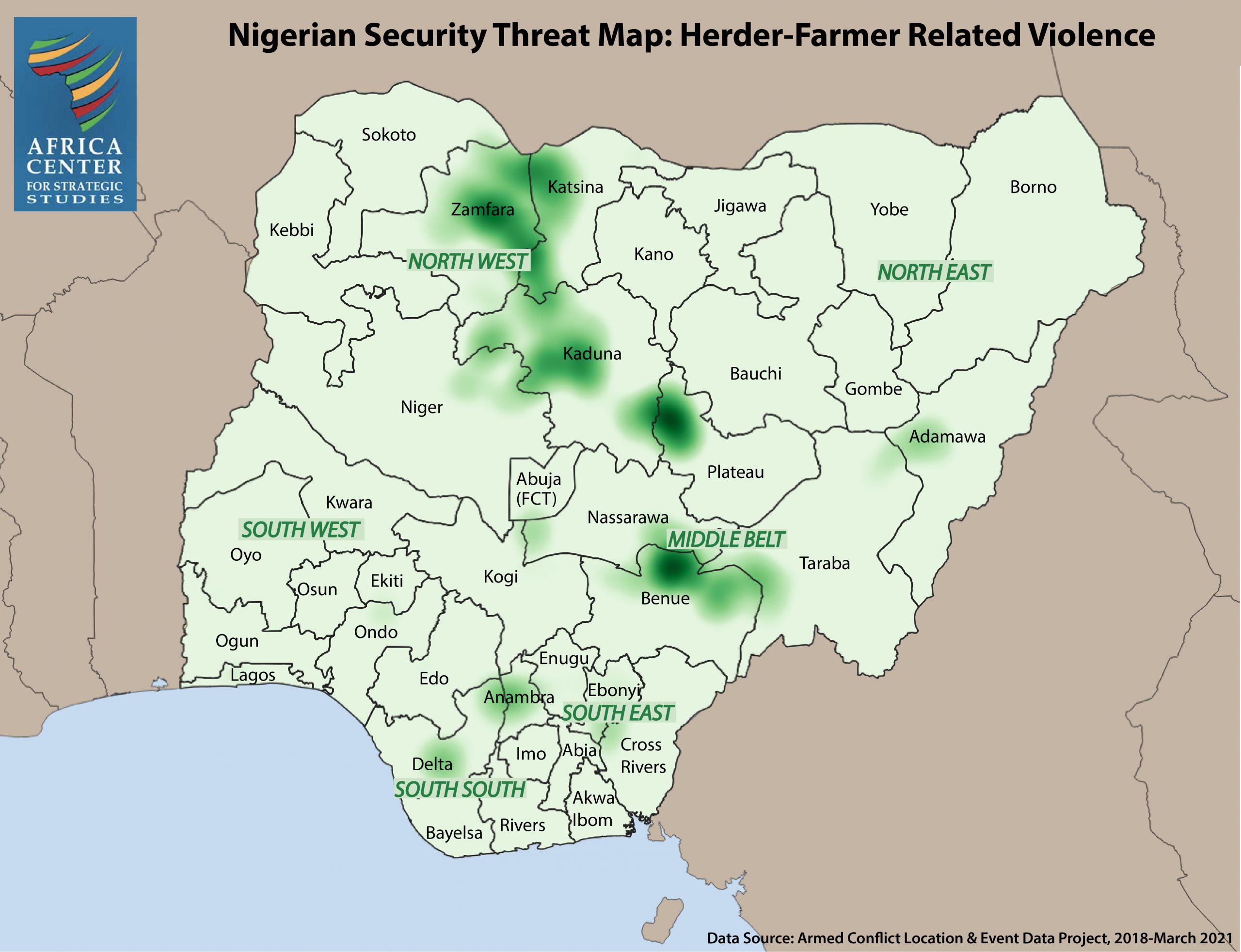

Farmer-Herder Conflict

Primarily affecting the Middle Belt and North West states, clashes between farmers and herders over land have spurred the formation of ethnic militias, vigilante raids, and extrajudicial killings.

Historically, the North West and Middle Belt states have been the fertile plains and grazing lands of Nigeria where nomadic pastoralist and sedentary agriculturalist groups coexisted, traded, and turned to local peacekeeping mechanisms when land disputes arose. However, desiccation and large land allocations to estate owners in the North West have pushed herders off their historical grazing routes. Likewise, according to aerial analysis by the U.S. Geological Survey, land available for open grazing in Nigeria’s Middle Belt declined by 38 percent between 1975 and 2013, while the area dedicated to farming nearly trebled. These dynamics have been driven by climate shifts, exclusionary land policies, and population growth. Meanwhile, demand for meat supplied by the country’s herders is rising.

“Despite this frequent framing in communal terms, religion and regional affiliation are not primary drivers of conflict.”

This central swath of Nigeria is also where the northern socio-political zone of the country meets the southern zone. This is a region of cultural exchange where dozens of languages are spoken and where no individual group has a clear political majority—national election margins are the closest in Middle Belt states. National politicians, large land holders, and their allies in the press have seized on these dynamics to politicize clashes between farmers and herders and between so-called “settlers” and “indigenous” communities in the region. Conspiracy theories and claims of coverups and ethnic cleansing around violence in the Middle Belt are common—and recycled even by well-meaning humanitarian groups and analysts. Despite this frequent framing in communal terms, religion and regional affiliation are not primary drivers of conflict. This is demonstrated by the fact that Islam-practicing Fulani and Hausa militias are often adversaries in these communal clashes, especially in the North West.

The politicization of communal violence in Nigeria risks expanding the scope of ethnically organized militias. Already, violence between herding and farming communities is beginning to occur in states south of the Middle Belt. In places like Ibadan (Oyo State) and Isuikwuato (Abia State), negative Fulani sentiment that southern Nigerian politicians and news outlets have generated around the Middle Belt violence is being used by ambitious individuals to incite anti-Fulani protests and attacks by armed youth groups.

Militant Biafran Separatists

Revived Biafran secessionist activities have escalated in recent years, leading to violent clashes between Nigeria’s security forces and militia groups resulting in dozens of deaths. Well known for its underground radio presence in the South East, the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) established what it calls the Eastern Security Network (ESN) in December 2020 to act as a paramilitary force in the region. Based on their rhetoric and goals broadcast on social media, this group seems more focused on mobilizing grievances against Fulani herders than advocating for autonomy in the region. ESN has declared that it will enforce a ban on grazing in the South East, stoking anti-Fulani sentiment. Nigerian courts have upheld IPOB’s designation as a terrorist group.

Nigerian security forces and ESN have clashed in a series of skirmishes in 2021 that have resulted in the deaths of several civilians in what has become known as the Orlu crisis. ESN has inflamed tensions by killing police officers at checkpoints in several locations in the South East. These back-and-forth raids and attacks risk plunging the region into a crisis similar to the Anglophone-Francophone conflict across the border in southwest Cameroon.

Asari Dokubo, the former leader of the Niger Delta Peoples Salvation Front, announced the formation of a Biafra Customary Government in 2021. Dokubo is now aligned with the militant separatist group, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB), as part of an apparent rivalry with IPOB. These developments portend increasing tensions with Nigerian security forces in the South East.

“Most pro-Biafra groups in the South East region are committed to nonviolence.”

South East Nigeria is still haunted by the memories of the country’s civil war (1967-70), when over a million people, including many civilians, died. This brutal conflict has had enduring ramifications for the region and the Nigerian state. To many Igbo people, whose parents and grandparents were part of the struggle for Biafra, the land in the South East is hallowed and still worth agitating for fuller control. However, most pro-Biafra groups in the South East region are committed to nonviolence and champion the cause of greater autonomy by peacefully protesting corruption, neglect, and arbitrary violence on the part of the Nigerian federal government. Despite disinformation produced by militant secessionists claiming that a return to civil war is imminent, the crisis is not nearly on the same scale as it was in the 1960s.

Human rights groups have documented Nigerian military and police using excessive force against pro-Biafran protestors, including killing 150 IPOB supporters and members in 2015 and 2016. On the 49th anniversary of the declaration of Biafran independence, in 2016, security teams that included members of the military opened fire on a parade in Onitsha, killing at least 60 people. Violence against civilians by Nigeria’s security forces has contributed to motivating young men in the region to join the militant groups.

Piracy

Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea is now the worst in the world, accounting for over 95 percent of crew members kidnapped. There were 35 recorded piracy events off the coast of Nigeria in 2020. These figures likely only represent a fraction of the incidents, given that ship owners have incentives to downplay the risk to avoid increasing insurance premiums. The groups behind these attacks are shadowy, but a number of pirate enterprises are known to be connected to the armed groups that have for decades sabotaged pipelines and kidnapped oil workers in Nigeria’s Delta (South South and South East regions). Groups like the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) have been difficult to address through security operations alone due their decentralized and leaderless structures, local support, and their tactics of striking quickly and disappearing into the region’s riverine labyrinth. Equipped with arms and speedboats and countered by oil companies spending millions of dollars on private security to protect oil infrastructure, some of these groups have begun venturing out of their swampland hideouts to board international ships in the Gulf of Guinea before retreating to their coastal bases with kidnapped crew members to negotiate ransoms paid from abroad.

Historically, groups in the Niger Delta have claimed to be motivated by the actions of multinational oil companies, which have polluted and impoverished the region. There is a lineage of righteous anger in the Niger Delta over this situation that has been voiced by likes of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni people. Many fishers and farmers in the region have had their livelihoods destroyed by contaminated land and water. Moreover, recent court rulings have declared that oil companies are responsible for the environmental degradation.

Today, however, profit from kidnappings appears to be the primary motivation for the piracy branching out into the Gulf. Declining oil prices also meant that kidnapping became more lucrative than siphoning crude oil from pipelines.

Security Sector Violence against Civilians

Police and military violence against civilians are a persistent impediment to sustainable peace in Nigeria. In 2020, nationwide #EndSARS protests, led by young people, transcended the country’s religious, ethnic, and political divides and demanded an end to police abuses, particularly the dissolution of the unaccountable Federal Special Anti-Robbery Squad (FSARS). This division of the national police force was originally set up to address the problem of organized criminal gangs across the country. Over time, however, FSARS became known for extorting Nigerian citizens and committing human rights abuses. In a vivid illustration of this, security forces opened fire on #EndSARS protesters in October 2020 to shut down marches and sit-downs across the country.

While FSARS has been in the spotlight recently, Nigeria’s State Security Service (SSS) has regularly harassed and detained journalists with impunity, including invading a courtroom to re-arrest a defendant whom the judge had ordered be set free. When protestors or fact-seekers get too close to the levers of power and privilege, it is often the SSS—directly overseen by the president—that intervenes. Another unit close to the executive—the Presidential Guard Brigade—was revealed to have shot and killed dozens of Shia marchers from the Iranian-backed Islamic Movement in Nigeria in Abuja in 2018. The protesters were demanding the release of their leader (who was still detained despite Nigerian courts ordering him freed).

A protest against the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) in Lagos. (Photo: TobiJamesCandids)

Many violent episodes between security forces and civilians take place in Nigeria’s cities. Nigerian security forces have frequently demolished urban neighborhoods and displaced vulnerable residents as a means of making way for upscale private developments. This creates insecurity for thousands of Nigerians and contributes to instability in the country’s cities. Many of these clearances are unannounced and illegal, but they go forward despite residents having long and legitimate tenancies and despite judges’ injunctions. Land deals and developments are at the center of organized criminal activities and corruption in Nigeria. As Nigeria’s cities continue to rapidly grow—they are now home to over half of the country’s 200 million citizens—low levels of trust in police and security forces are becoming a major challenge to building stable and resilient cities.

Need for Multi-Dimensional Responses

The diversity of Nigeria’s security threats will require an innovative set of solutions adapted to each context. This will entail understanding the local dynamics of each threat and integrating them into a multidimensional national security strategy.

As Nigeria’s challenges are largely domestic in nature, this national security strategy will require active citizen engagement. Citizen cooperation may be the most essential element of a successful response in each context. Yet, in nearly every instance, Nigeria’s security forces are starting from a deficit of trust. Indeed, security force violence against citizens is often viewed as part of the security problem. Remedying this and building trust with citizens will be a top and ongoing priority of any national security strategy.

“Citizen cooperation may be the most essential element of a successful response.”

The domestic nature of these threats also highlights the importance of an integrated security response that encompasses expanding access to government services, social development, and job creation. Integrated security also entails widening access to justice. Accessible and trusted justice mechanisms can serve as a vehicle for conflict mitigation as well as defusing tensions between communities or with the government. Rulings by courts, in turn, must be respected and upheld by security actors. This review reveals, especially with regards to security sector violence against civilians, repeated instances of security services disregarding judicial rulings, thereby exacerbating social tensions and undermining the rule of law.

Another recurring challenge observed across multiple security contexts is the need to sustain a security presence in outlying areas. Nigerian security forces have repeatedly been able to clear militant groups from territory they’ve held – be it Boko Haram in the North East, criminal groups in the North West, or pirates and armed gangs in the South West or South South. However, the inability to sustain a security presence creates a security vacuum that has enabled these militant groups to regroup and revive their predatory activities. Communities that are caught up in the middle of these shifting security frontlines are left in a vulnerable position. For Nigeria to turn the corner vis-à-vis these militant groups, the government and security forces will need to be able to sustain an ongoing and accountable security presence in these contested regions.

Land management is another crosscutting issue shaping Nigeria’s security challenges. Currently, there are on average over 500 people per square mile living in Nigeria. The country’s population is projected to double to 400 million in the next 30 years, spiking its population density to levels currently seen in Israel and India. Already, many Nigerians are struggling to find sufficient resources and opportunities to imagine a secure future for themselves and their families. Nigeria recently surpassed India as home to the most people living in poverty in the world, and its unemployment rate is 33 percent. Reflecting the multidimensional nature of Nigeria’s security threats, negotiating access to land will be an increasingly critical factor in managing Nigeria’s security landscape moving forward.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The Nigerian State and Insecurity,” Video Roundtable, February 17, 2021.

- Olajumoke (Jumo) Ayandele, “Confronting Nigeria’s Kaduna Crisis,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 2, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Spike in Militant Islamist Violence in Africa Underscores Shifting Security Landscape,” Infographic, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 29, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa Target Nigeria’s Highways,” Infographic, December 15, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “#EndSARS Demands Nigerian Police Reform,” Infographic, November 10, 2020.

- Oluwakemi Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 31, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 2016.

- Adeniyi Adejimi Osinowo, “Combatting Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea,” Africa Security Brief No. 30, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 2015.

- Joseph Siegle, “Boko Haram and the Isolation of Northern Nigeria: Regional and International Implications,” in Boko Haram: Anatomy of a Crisis, Ioannis Mantzikos, ed., E-IR, 2013.

- Michael Olufemi Sodipo, “Mitigating Radicalism in Northern Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 26, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 2013.

- Chris Kwaja, “Nigeria’s Pernicious Drivers of Ethno-Religious Conflict,” Africa Security Brief No. 14, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2011.

More on: Combating Organized Crime Countering Violent Extremism Identity Conflict Maritime Security Police Sector Reform Security Sector Governance Nigeria

Militant Biafran Separatists

Militant Biafran Separatists Piracy

Piracy Security Sector Violence against Civilians

Security Sector Violence against Civilians